" ... I attempt a direct attack on the Hydra whose serpentine heads wreak havoc throughout the intellectual culture of modernity - in science, in criticism, in ethics, in political, in political thinking, almost anywhere you look. I call the Hydra "epistemology," which sounds rather unfair, because that´s the name of a problem area, and what I have in my sights must be something in the nature of a doctrine. But the name is deserved, in the sense that the philosophical assumption it designates gives epistemology pride of place. These are the assumptions that Decartes gave articulation to; central is the view that we can somehow come to grips with the problem of knowledge, and then later proceed to determine what we can legitemately say about other things: about God, or the world, or human life. From Descartes´s standpoint, this seems not only a possible way to proceed, but the only defensible way. Because, after all, whatever we say about God or the world represents a knowledge claim. So first we need to be clear about the nature of knowledge, and about what it is to make a defensible claim To deny this would be irresponsible.

I believe this to be a terrible and fateful illusion. It assumes wrongly that we can get to the bottom of what knowledge is, without drawing on our never-fully-articulate understanding of human life and experience. There is temptation here to a kind of self-possessing clarity, to which our modern culture has been almost endlessly susceptible. So much so that most of the enemies of Descartes, who think they are overcoming his standpoint, are still givining primacy of place to epistemology. Their doctrine about knowledge is different, even radically critical of Descartes, but they are still practicing the structural idealism of the epistemological age, defining their ontology, their views of what is, on the basis of a prior doctrine of what we can know."

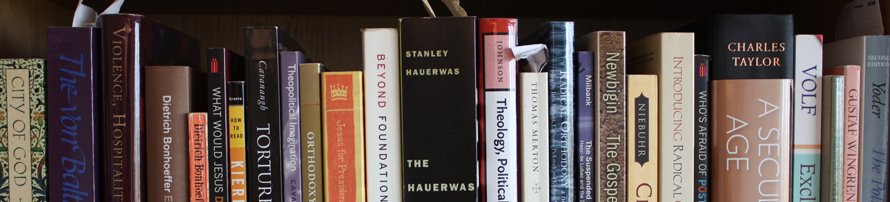

- Charles Taylor. Philosophical arguments. Harward University Press, 1995. s. vii